Globalisation is simply the

expression of the increasing division of labour

It may also now be seen clearly what

globalisation is. Globalisation is not some special process and it is not

fundamentally about national boundaries. It is simply the extension of the

division of labour under circumstances in which the world economy has become so

large and so interconnected that an efficient division of labour can no longer

be carried on simply within national boundaries.

The development of continental

scale integrated economies

If I may present another aside, this

process also gives a clear indication of what is the present stage of the

development of division of labour. The era where West European sized national

economies were capable of creating the most efficient

division of labour and economies of scale has been left behind. The strength of

the United States is that the US was the first modern continental-sized

economy. The Soviet Union was in a sense the second continental scale economy –

but this one collapsed and was balkanised. The third continental-scale economy

is China. The fourth continental scale economy is India. And at the present

time Western Europe is rather failing to create the fifth continental-scale

economy – but the future will see what happens.

Historical development of a

rising level of investment

Having spent a long time examining the

most powerful productive force, the social division of labour, I now want to

analyse in more detail the second most powerful force in economic growth –

investment.

Slide 30 shows the historical tendency of

the proportion of the economy devoted to investment to rise. This was a process

identified by Adam Smith, was analysed at great length by Karl Marx, and was

one of the foundations of the economic theories of John Maynard Keynes. As can

be seen this process has been operating over the entire period for which it is

possible to get serious statistical economic data and it may therefore be taken

as one of the most well established of economic trends.

Slide

30

To summarise briefly the chief features,

and periods, shown in Slide 30, the first economy for which it is possible to

calculate relatively meaningful statistics for the proportion of the economy

devoted to investment was England in 1688. The reason for this is because

England was about to become the world’s first industrial state, it was the most

developed economy in the world, and so it had the best statistics. There is a

discussion among economic historians whether at that time England invested 5%

of GDP or 7% of GDP but this does not matter for present purposes because it is

so low compared to the levels of investment in a modern economy. This 5-7% of

GDP devoted to investment, however, allowed England to create the first

industrialised economy in the world.

Slide 30 makes clear what happened in the

next 300 years – a constantly rising proportion of the economy devoted to fixed

investment which has had more and more rapid rates of economic growth

associated with it.

Here we may also note that China

underlines and characterises its system as having ‘Chinese characteristics’ –

therefore ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’, a legal system ‘with

Chinese characteristics’ etc. I would also insist as a fundamental

methodological principle that every country, indeed every entity, is unique -

so each respective country will have ‘US characteristics’, ‘British

characteristics’, ‘Russian characteristics’, ‘South African characteristics’

etc. But, as already discussed, these are unique combinations of universal

processes.

China’s current level of investment, of

more than 40% of GDP, therefore indeed has very specific ‘Chinese

characteristics’. But it is also the continuation of a trend of 300 years of

history of rising proportion of the economy devoted to investment.

To take some of the key stages of

development in this historic process

England

achieved from around 1688 a level of 5-7% of GDP devoted to fixed investment

generating an rate of economic growth of around 2%.

The

US, from the aftermath of the Civil War onwards, devoted about 18% of GDP to

investment, enabling it to grow at about 3.5% a year as opposed to England’s

2%. Consequently, during the 1870s, the US overtook Britain to become the

world’s largest economy.

After

World War II Germany invested about 25% of GDP, generating 5% annual economic

growth and creating the post post-war German ‘economic miracle’.

In

the 1960s and early 1970s Japan invested about 30% of GDP and its economy grew

at 7- 8% a year.

China

now invests over 40% of GDP and its annual average growth rate is 10%.

This historical trend is so clear

doubtless in the future some economy will invest 50% of GDP and grow

sustainably at 12% a year. But that’s for the future. Presently China has the

world’s highest investment rate and the world’s fastest growth rate.

China

and India’s efficiency in the use of investment for growth

As we have already seen that, after the

division of labour, investment is the most powerful contributor to economic

growth it is, of course, evident why a rising level of investment is associated

with rising economic growth rates. However to use investment efficiently the

economy has to be orientated towards international market.

This was a mistake of the Soviet economy.

The Soviet economy was orientated towards its own internal domestic market and

therefore could not use investment efficiently. However provided that the

orientation to the (in the modern world necessarily international) division of

labour is maintained, and to the efficient use of investment, it is the

quantitative amount invested that determines how rapidly an economy grows. And

considering the intermediate/long term trend, after participation in the

international division of labour, it is the proportion of the economy as that

is devoted to investment which is decisive. This is what studying economic

history shows as well as modern econometrics.

In order to illustrate this in more

detail consider the two most rapidly growing modern economies – China and India.

Both have achieved highly efficient use of investment from the point of view of

generating economic growth. What is technically known as the Incremental

Capital Output Ratio (ICOR) for both countries is 3.7 – this is the percentage

of GDP that has to be invested for the economy to grow by 1% is 3.7% (i.e.

China and India both have a ratio of investment to growth of 3.7:1 - the lower

the number the more efficient the investment).

China and India’s levels of efficiency of

investment, from the point of view of economic growth, are among the best ever

achieved for a sustained period – in the case of China it has been sustained

for over two decades and in India for a decade and a half. The reason that the

Chinese and Indian economies grow so fast is therefore simple: they both have a

high efficiency of use of investment and a very high proportion of GDP devoted

to investment.

To show this Slide 31 simplifies the

previous graph to show just the post-World War II rates of investment of China,

India and the US. As may be seen China invests more than 40% of GDP, India

invests around 35% of GDP, and the US invested around 18% of GDP prior to the

international financial crisis – following which its rate of investment fell

further. On the basis that the rate of investment in the

United States is only half that of China and India the US cannot possibly match

their growth rates or increasing competitive power.

It is the consequence of this new

situation in the world economy that led directly to the international financial

crisis.

Slide

31

The declining competivity

of the US economy

A historical feature of the US was its

extremely stable rate of growth - linked to a stable rate of investment. The US economy, with significant fluctuations

only in 1929 and during the two World Wars, has been growing at close to 3.5% a

year for the last 150 years. It was the most predictable growth rate actor in

the world economy for the simple reason that the US was the most powerful

country in the world. The US was therefore normally able to retain stability

even if problems were pushed onto other economies. This latter possibility will

be looked at in detail later in analysing the situation in regard to Japan. But

to summarise what will be demonstrated at length later, the economic policies

pursued by both Nixon and Reagan, for example, had deeply damaging consequences

for Japan – Nixon via the oil price increase of 1973, which the US in fact

supported, and a forced increase in the exchange rate of the yen in 1971, and

Regan in forcing Japan to adopt very low interest rates, to aid the US economy

after the 1987 stock market crash, which culminated in Japan’s ‘bubble economy’

and post-1990 economic crisis. Historically, with the exception of 1929, the

peacetime US economy was able to maintain its own stability even when other

economies suffered problems. But now the US has been radically overtaken in its

level of investment by a whole series of countries, and its competivity

has declined – the consequences of this led directly to the financial crisis.

Why is it possible to know that the US

economy is increasingly uncompetitive and what happens under such

circumstances? Surveys of business people saying that the US economy is the

most competitive in the world, or citing the evident fact that in certain spheres

of high technology industry, or in the military sphere, the US is the most

advanced in the world are not relevant and frequently used to divert attention

from the real process of the decline of US competivity.

Economic and business competition does not take place via opinion surveys or

newspaper articles, or individual sectors of production. It takes place in

overall competitive markets and is reflected in the monetary flows that result

from these.

The way to know whether

the US economy can compete or not is to examine its balance of trade – which in

turn dominates the US balance of payment.

The situation of this is shown clearly in Slide 32, which charts the US balance

of trade as a percentage of GDP.

As may be seen until the 1970s the US

economy was relatively competitive – that is its balance of trade balanced.

From the beginning of the 1980s onwards, however, the US economy became

progressively less competitive – the US balance of trade moved into

progressively wider deficit. The final upward movement at the end of the graph,

the narrowing of the balance of trade deficit, was the effect of the financial

crisis and will be analysed later.

Slide

32

Financial inflows into the US

The US trade deficit raises the question

of how this was financed, and this in turn leads directly to the financial

crisis and to issues already analysed concerning China and the US.

To show the link between the trade and

financial flows processes Slide 33 charts the long term change in the exchange

rate of the dollar against the yen and against the Deutsche Mark and its

successor the euro.

As can be seen from Slide 33 there are

three post-World War II periods in the development of the dollar’s exchange

rate.

The first is from immediately after the

Second World War to the early 1970s. This is the period of fixed exchange rates

under the Bretton Woods agreement. Of course in that

period the exchange rate of the dollar is stable.

The second period is that of the

relatively rapid devaluation of the dollar from the early 1970s until 1980.

The third period is that from 1980 until

the early 2000s - in which there is again a stable exchange rate of the dollar.

This third phase is sometimes referred to as ‘Bretton

Woods 2’. It differs from the original Bretton Woods

period in that there is no formal agreement to have fixed exchange rates but

the actual reality is that the dollar’s exchange rate has not moved greatly –

there are short term fluctuations but no major overall movement.

Slide

33

How, therefore, was the dollar’s exchange

rate stabilised under the conditions shown in Slide 32 of a sharply

deteriorating US balance of trade, and also a US balance of payments deficit?

If trade had been the sole determinant then the outflow of dollars, due to the

balance of payments deficit, would have led to a decline in the exchange rate

of the dollar. For the dollar’s exchange rate to remain stable there had to be

an equal inflow of finance into the US to match the outflow due to the balance

of payments deficit. This, of course, is what occurred - as shown in Slide 34

which charts the

inflow of portfolio investment into the US.

The danger is evidently that the graph in

Slide 34 might be interpreted as that of ‘a financial addict’. That is the

inflow of finance into the US rose constantly as a percentage of GDP. This was

bound to break down at some point – and it did so in the financial crisis as

will be seen below.

Slide

34

Why was the dollar not devalued?

From the data above the interrelation of

the financial and competivity aspects of the US

balance of payments is clear. But a question is posed. Why from the 1980s

onwards did the US break with the policy of devaluing the dollar that it has

had used in the 1970s to maintain equilibrium in its balance of payments?

While the US, due to its too low rate of

investment, was gradually loosing competivity it

could theoretically have compensated for that, in terms of maintaining a balance of payments equilibrium, by dollar devaluations.

If the US lost 1-2% competivity each year due to its

lower investment rate, it could have devalued the dollar by 1-2% a year and its

balance of payments would have remained in equilibrium. There would therefore

have been no need for a very large huge inflow of finance from abroad. This is

what happened during the 1970s – the second period of exchange rate movements

analysed above. During the 1970s the US devalued the dollar and its balance of

payments remained in balance despite the fact that its economy’s underlying competivity was declining.

Why, therefore, did the US not continue

this course pursued during the 1970s? Why did it turn from the 1980s onwards to

ending the dollar devaluation and instead maintained a relatively stable

exchange rate?

The answer lies in politics. It’s very

easy to propose theoretically that the dollar should devalue. But it is

drastically politically unpopular in the United States. To see this simply note

who were the two US presidents who presided over the decline in the exchange

rate of the dollar? First Nixon - who was driven from office in disgrace, and

then Carter who was considered as the worst and most ineffectual post-World War

II US president (perhaps prior to George W. Bush).

It might appear that the reasons for

Nixon and Carter’s unpopularity were due to contingent factors – Nixon because

of the Watergate break in and Carter due to the Iran hostage crisis and other

factors. But when the ‘accidents’ happen against the same background there is a

pattern to them – someone said that ‘history is the natural selection of

accidents’. The economic basis of the unpopularity of Nixon and Carter is

clear. Devaluing the dollar puts up the prices of imports into the United

States, increases inflation, and cuts the living standards of the population.

US competivity was maintained by a declining exchange

rate of the dollar under Nixon and Carter but at the expense of massive

political unpopularity.

Reagan and Clinton reversed this policy,

stabilised the dollar, and were both re-elected. Under both presidents the competivity of the United States went down, the US balance

of payments moved into drastic deficit - and both were re-elected. Both in

essence were popular because they borrowed huge sums of money abroad – because

this was this which, as shown in Slide 34, stabilised the dollar.

As long as loans flowed in popularity continued.

It is an analogy to an international

credit card financing US consumption on a huge scale. Provided you never think

about repayment you feel good on a credit card as you spend above your income.

The problem comes when, worst case, you have to repay debt or, slightly less

serious but still very uncomfortable, when the credit card company will no

longer lend you money. In that case you have to drastically reduce expenditure.

This is what happened in the financial crisis.

To show this process Slide 35 shows what

happened to the US monthly balance of trade deficit in dollar terms. As can be

seen it widened progressively until 2005 when it reached almost $70 billion a

month (equivalent to over $800 billion a year), began to reduce slightly after

this, and then from mid-2008 violently contracted under the impact of the

international financial crisis to around $30 billion a month – it has since

widened again slightly.

Recall that to prevent the dollar

devaluing, under conditions where there is an outflow of dollars, from the

balance of trade and balance of payments deficits there must be an equal inflow

of finance in the US. But the contraction of the trade deficit, which dominates

the US balance of payments, meant that the inflow to stabilise the dollar was

reduced by several hundred billion dollars a year – or to put it another way

the inflow of goods and services that were not being paid for, except by

borrowing, shrank drastically. Borrowing on the ‘international credit card’ was

cut abruptly. Consequently expenditure by the US economy had to be reduced.

Slide

35

The reduction of expenditure in

the US

Confronted with situation of a forced

reduction in expenditure the US economy could have responded in one of two ways

– or by a combination of the two. First the US could have reduced consumption expenditure. This would

have meant a reduction in personal consumption or reduction in government

expenditure – including military expenditure which, from an economic point of

view, is government consumption. Or alternatively the US could have drastically

reduced expenditure on investment.

Which actually occurred was examined

earlier and I reproduce Slide 9 above as Slide 36 to recall the outcome. As

already analysed the overwhelming bulk of the reduction in US expenditure took

place in investment. The fact that in Slide 36 the positive movement in net

exports, i.e. the reduction in the trade deficit, and the fall in fixed

investment are almost the same in their scale but with reversed signs shows the

essence of the reaction of the US economy to the financial crisis. The US

redirected resources from investment into net exports while leaving consumption

relatively little changed. US personal consumption fell by a relatively small amount,

US military expenditure actually increased, but investment was allowed to

decline severely.

Slide 36

The medium and long term result of this

outcome is evident from data give earlier. As has seen the underlying cause of

the decline in competivity of the US is its too low

rate of investment compared to its competitors – above all compared to China.

The effect of the financial crisis, by leading to an even further fall in US

investment, has therefore made the structure of the US economy worse.

US competitive policy to attempt

to slow down China’s economy

As the level of investment in the US

economy has actually fallen it is evidently unable to accelerate its own

economic growth to compete with China. However it is evident

that that the US will not give up without a competitive struggle its position

as the world’s largest economy. Another way the position of the US can be

maintained is therefore to attempt to slow down China’s economy.

There are three major means to attempt to do this at present, complimented by

several minor ones.

The major means to attempt to slow down

China’s GDP growth rate are:

To

attempt to force the exchange rate of China’s currency, the RMB, to go up too

fast and too rapidly.

To

attempt to force China to cut its investment rate.

To

attempt to discourage foreign investment from entering China.

The more minor, but significant, ones

are:

To

prevent China having access to foreign technology.

To

prevent China buying assets abroad.

Each of these instruments has been used

by the US as a competitive policy previously in regard to other countries and

each will be analysed in turn.

The Asian dimension of the

financial crisis

The competitive means used by the US to

attempt to slow down China’s economy can best be understood if it is realised

that there is a specific Asian dimension to the present financial crisis. From

within Asia this could indeed be described as the ‘third great Asian financial

crisis’ – the previous two being the situation in Japan after 1973 and the debt

crisis in South-East Asia in 1997, which of course rolled into Russia in 1998

(I was here at the time of the rouble devaluation and remember it vividly). We

will therefore move from looking at the world dimensions of the financial

crisis to looking at its specifically Asian aspect.

I have set out schematically these three

major Asian economic/financial crises:

The

first Asia financial crisis 1973-1990 in Japan.

The

second in 1997 in South East Asia.

The

third one is the current (international, since 2008) crisis.

To summarising the entire period of the

last four decades, Slide 37 shows the cumulative effect of the last forty

years, including these three Asian financial crises, on the changes in growth

rates of the four largest Asian economies – Japan, China, India and South

Korea.

What this chart graphs is not the absolute

rate of growth of GDP but the change in the rate of GDP growth for each

country compared to the beginning of the 1970s. The 0% line on the graph

therefore does not mean 0% absolute growth. It means that the growth rate was

the same as 1970s. If the curve is

moving upwards the economy has accelerated, if the curves are going down an

economy is growing more slowly.

As can be seen the big losers of the

successive economic developments and financial crises in the last forty years

in Asia were South Korea, the growth rate of which slowed down by 4-5% a year,

and above all Japan, the growth rate of which slowed down by 8-9%. Indeed

finally Japan’s economy is today essentially static. The big gainers,

that is the countries which went through the Asian crises successfully,

were China and India – the economies of both of which accelerated

significantly.

The three Asian financial crises will be

considered in chronological order.

Slide 37

1973-1990 Japan’s economic and

financial crisis

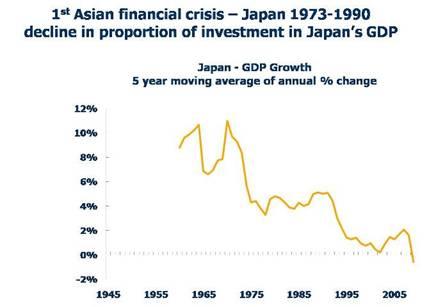

During the period 1973-1990 Japan

accumulated the preconditions of a financial crisis which has become among the

most devastating for a major economy in modern economic history. The dimensions

of this crisis, in terms of slowdown in rate of growth of GDP may be seen in

Slide 38. This shows the deceleration of Japan’s economic growth - from an

average 8-9% a year in the early 1970s, first to around 4% a year in the 1970s

and 1980s, and then to essentially zero in the 1990s and beginning of the 21st century. The annual GDP growth in the graph

is expressed as a five yearly moving average to remove the effect of purely

short term fluctuations.

Slide 38

What international conditions caused this

drastic slowdown? And how did each strengthen the competitive position of the

US economy compared to Japan’s?

The first development, which, it should

be said immediately, would not have the same effect on the

relative competitive positions of Japan and the US today, was the drastic

increases in the price of oil in 1973 and 1979. At that time this benefited the

US economy, compared to its competitors, as the US was far less reliant on oil

imports than either Japan or its own situation today. The drastic oil price

rise therefore aided the US vis-a-vis

Japan. Today, however, the US has become far more dependent on oil imports and

an equivalent oil price increase would not aid it vis-a-vis

its competitors in the same way.

The second issue was the shift in the

exchange rates between the Japanese yen and the US dollar which started in the

period after 1971 and which is shown in Slide 39.

In Slide 39, in order to make a

comparison with China, the horizontal axis shows the number of months since a

rise in the exchange rate began. As can

be seen the exchange rate of the yen against the dollar has increased in the

period between 1971 and today by 300%.

To give more precise chronology, the

yen’s exchange rate went up in two periods. The first, between 1971 and 1985,

saw an increase in the yen’s exchange rate of around 50% compared to its

pre-1971 rate. This was associated with the deceleration of Japan’s rate of

growth of GDP from 8-9% a year to 4% a year - as shown in Slide 38. After 1985

came a second, much greater, increase in the exchange rate of the yen to around

300% of its pre-1971 level. This was associated, as shown in Slide 38, with a

slowdown in the rate of growth of Japan’s economy eventually to essentially

zero. This huge increase in the exchange rate of the yen evidently helped

drastically slow the Japanese economy.

Slide 39

To make an international comparison,

Slide 40 shows the increase in both the exchange rate of the yen and the D-Mark/euro

against the dollar – the middle line, rising about 150%, is the German (and

then European) currency. The increase in the exchange rate of the German

currency against the dollar was about half that of the yen. The European

economies slowed, but not as drastically as Japan.

The US was well aware that an increase in

the exchange rate of a currency is a powerful instrument for slowing down an

economy – in 1961 the US had ensured a German currency revaluation, putting an

end to the extremely rapid growth rate of the post-war ‘German economic

miracle’.

The extremely sharp increase in the

exchange rate of the yen after 1971 did almost nothing to eliminate Japan’s

trade surplus – as a percentage of Japan’s GDP it is almost exactly the same

nearly forty years later as it was in 1971. But the increase in the exchange

rate of the yen broke the rapid rise of Japanese exports, which incidentally

had been matched by an almost as rapid a rise of its imports, thereby slowing

Japan’s entire economy. Forcing an increase in the exchange rate of the yen

therefore was of no use in decreasing Japan’s trade surplus but it was

extremely effective in slowing Japan’s economy – just as the enforced

revaluation of Germany’s currency had been in 1961.

To turn to a current issue the US

administration may, or may not, be genuinely deluding itself into believing

that an increase in the RMB’s exchange rate would decrease China’s trade

surplus – this is something we will look at later. But the US administration

must be aware, as it has had much previous experience of similar issues, that

an increase in the RMBs exchange rate might be very effective in slowing

China’s economy. We will look at that issue in detail later.

Slide

40

Finally, regarding the first great Asian

financial crisis, consider the internal development of Japan’s economy after

1973.

It was analysed earlier that the primary

source of GDP growth, after increasing participation in division of labour, is

increase in fixed investment. Slide 41 therefore graphs the percentage of

Japan’s GDP devoted to fixed investment. As may be seen pattern is clear and in

line with econometric

studies on the sources of growth shown earlier. The extremely rapid growth of

Japan’s economy in the period from the 1950s up to 1973 was associated, as

would be expected from the econometric data, with a very high, and until 1973

rising, proportion of its economy devoted to investment – reaching a peak of

35% of GDP. After 1973 the share of Japan’s economy devoted to investment fell

almost continuously until now it has reached a level of only around 20% of GDP

– indeed in the 4th quarter of 2009 it actually fell below 19%.

With this drastic decline in the share of

investment in the economy Japan was, of course, incapable of achieving the

rapid economic growth rates it had achieved prior to 1973.

The achievement of US competitive

advantage was therefore clear. By forcing up the exchange rate of the yen,

initially through the threat of tariffs used by Nixon and later by other means,

Japan’s economy was slowed. By the reduction in the rate of investment Japan

became incapable of the very rapid economic growth which had allowed it to

narrow the gap between the size of its GDP and that of the US. The combination

of enforced exchange rate increases and reduction in investment, therefore,

allowed the US to gain a decisive strategic competitive victory over Japan.

Slide

41

(next part)

(next part)